There’s been no substantive announcement but the Tasmanian state government has dropped many hints that bus rapid transit might be the future of public transport in Hobart. Here we take a look at what is known at this early stage.

What is bus rapid transit?

Bus rapid transit (BRT) is not a standard bus network. Instead it has a number of features which mean it functions as a high capacity and high frequency public transport system much like light rail.

Typical features

- Frequent services — aiming for passengers to turn-up-and-go instead of needing a timetable.

- High capacity buses — usually articulated buses with low floors and spacious internal design.

- Relatively few stops — often designed more like train stations than typical bus stops.

- Dedicated bus roadways or lanes — often with traffic lights prioritising the buses at intersections.

- Features to improve the efficiency of passenger boarding — ticketing when entering the station rather than the bus, platforms at bus floor level, boarding through multiple doors.

BRT compared to other options

Bus rapid transit has pros and cons compared to the other forms of high capacity public transport like light rail and trains (aka heavy rail).

| Capacity | BRT typically carries less passengers per vehicle than light rail and much less than heavy rail. This can be offset by increasing frequency of services. |

| Number of stations | BRT and light rail tend to have more stations than heavy rail as the acceleration & deceleration of trains means they’re not efficient for short distances. |

| City shaping | Light rail does the most to encourage high density residential development due to its permanent infrastructure, closely spaced stations and because it’s seen as a high quality system. Heavy rail has somewhat less effect on urban renewal due to increased distance between stations. Bus rapid transit does less to encourage development, though high quality busways and stations can reduce this difference. |

| Infrastructure & capital investment | Both heavy and light rail require tracks, which often means digging up existing pavement as well as moving pipes and other utilities underneath. Bus rapid transit doesn’t require rails, though the frequent heavy vehicles may quickly damage pavement that isn’t reinforced. The size and speed of heavy rail means it is more likely to need tunnels and underground stations in dense areas like the Hobart CBD. It also means intersections with roads require level crossings with boom gates. Both light rail and bus rapid transit require intersections upgrades with prioritised traffic signals. All options require the construction of stations. They also all need improved feeder bus networks and active transport connectivity to be effective. Overall, these infrastructure requirements mean heavy rail has very high capital cost, bus rapid transit is the least expensive and light rail is somewhere in between. |

| Operational costs | Smaller capacity vehicles can mean BRT requires more drivers than light rail and therefore can have higher operational cost. |

| Risk | Lack of need for more specialised infrastructure like rails means there is less risk involved in constructing BRT than light and heavy rail. |

| Flexibility | BRT allows flexibility in ways that light and heavy rail doesn’t. For example, BRT buses can divert to roads if there’s a crash on a busway. As another example, standard buses could use BRT busways during times of especially high demand such as an event at a stadium. |

| Ride experience | Light & heavy rail typically offers a smoother and quieter ride than BRT. Modern electric buses on a smooth busway can reduce this difference to an extent. |

Trackless trams are essentially high quality bus rapid transit. The vehicles can be larger than typical BRT and are claimed to have better ride quality. They can potentially drive autonomously with an optical guidance system that follows lines drawn along their route. It’s relatively new technology with limited providers and therefore inherently higher risk.

BRT in other cities

Bus rapid transit is used in hundreds of cities around the world. A few notable networks include:

- Brisbane — The new Brisbane Metro, despite its name, is a high quality bus rapid transit network. Electric buses with a capacity of 150-170 people will travel up and down Brisbane’s existing busways. Suburban bus routes will connect to the Metro instead of travelling through the city centre as many of them currently do.

- Bogotá — The TransMilenio is famous for the change it triggered in the capital of Colombia in the early 2000s and inspired many other cities. It carries 2 million people per day. Amazingly, its capacity reportedly far exceeds light rail and exceeds all but the highest capacity heavy rail.

- Jakarta — The capital of Indonesia has the largest BRT in the world at 210 km.

- Perth — In November 2023, City of Stirling imported a trackless tram from China and tested it in a carpark with a view to a potential route connecting the Perth CBD to Scarborough Beach. They considered it a success and are now aiming for state or federal funding to implement the project for real.

What’s the plan for Hobart?

The plan for bus rapid transit in Hobart is becoming clearer as more details appear in planning documents. It’s all very much subject to change though.

Corridors & routes

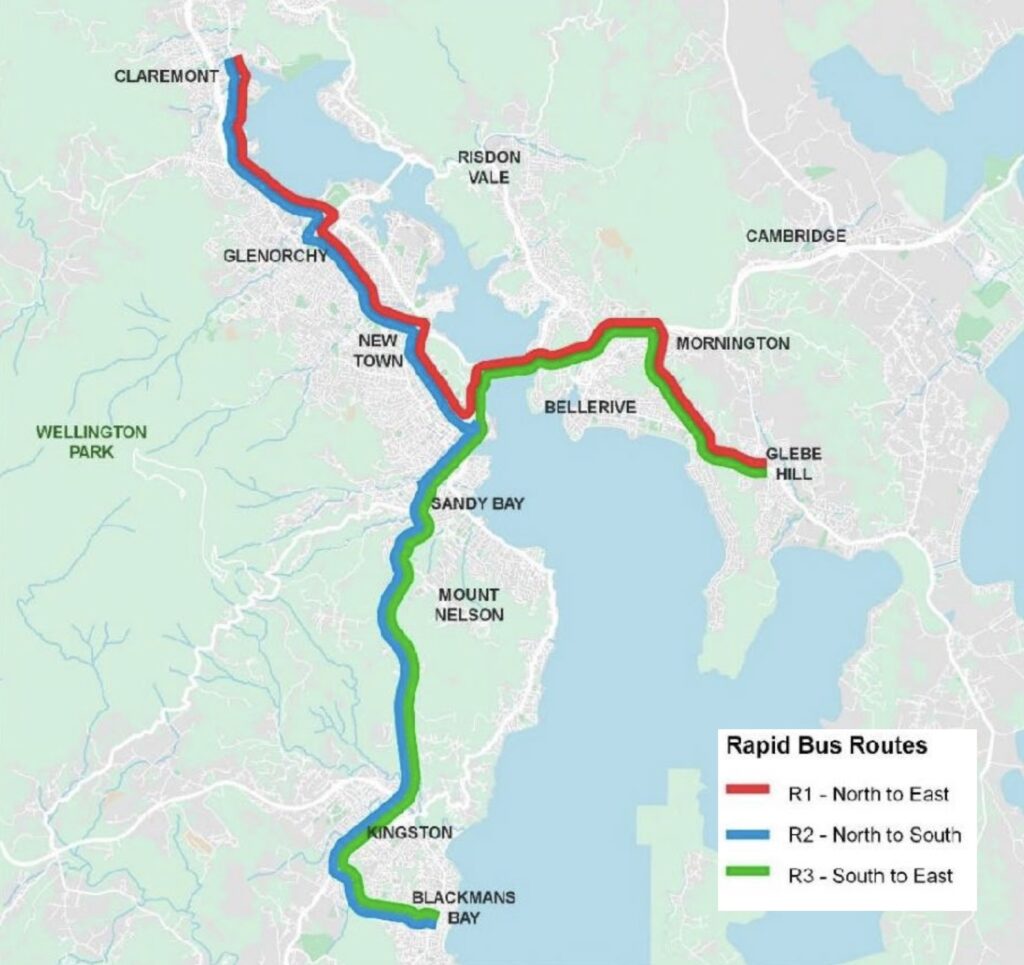

The BRT will service three corridors: north, south and east. The three corridors meet at a central interchange near the convergence of the Brooker Highway, the Tasman Highway, and Davey & Macquarie Streets.

Buses will travel along a corridor into the CBD and then continue on one of the other two corridors back out of the city. This results in the three routes shown in the map — North to East, North to South, South to East — and means buses won’t need to turn around in the city. It’s also beneficial for passengers. For example, a passenger boarding in Kingston could choose a bus that will take them to either Glenorchy or Bellerive without changing in the city.

Northern corridor

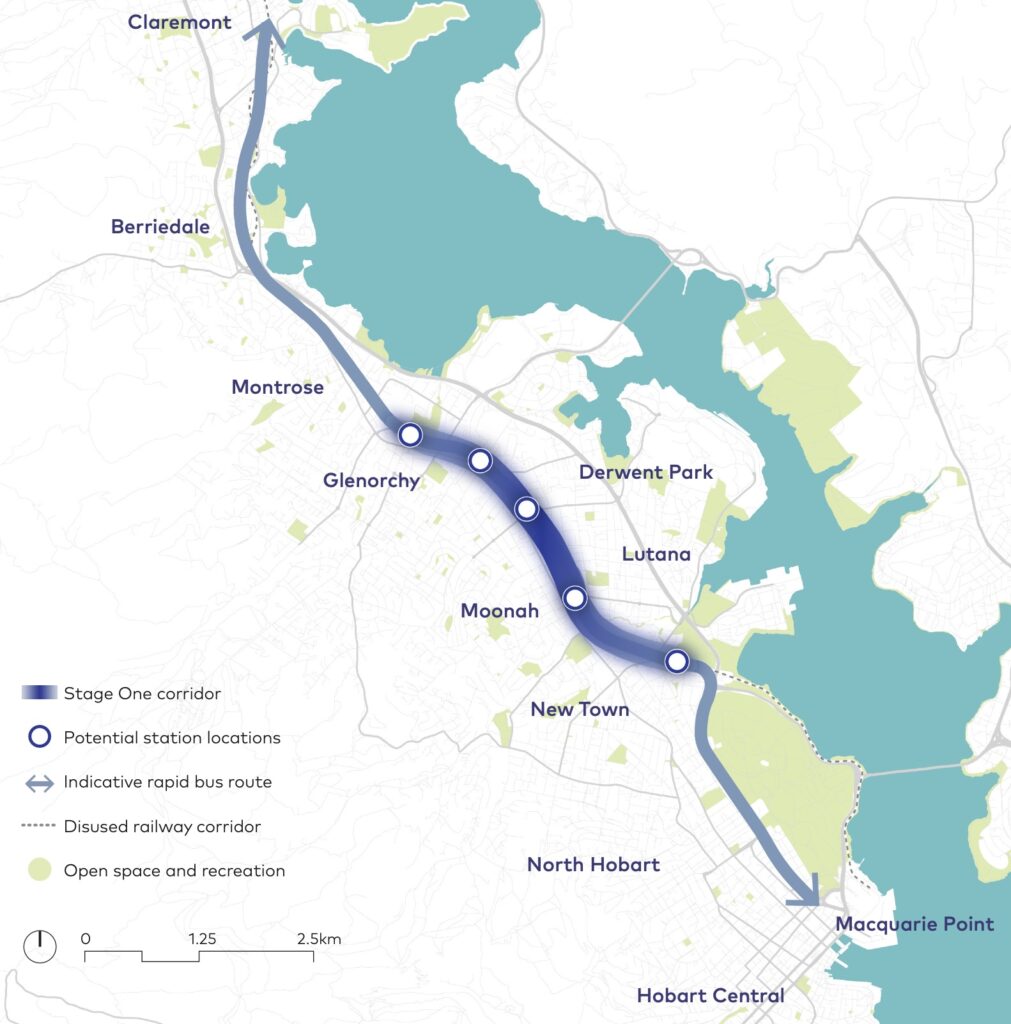

The northern corridor starts in Claremont. It seems as though it will follow the existing rail corridor through Berriedale, Montrose, Glenorchy, Derwent Park and Moonah to New Town.

The map shows five potential station locations.

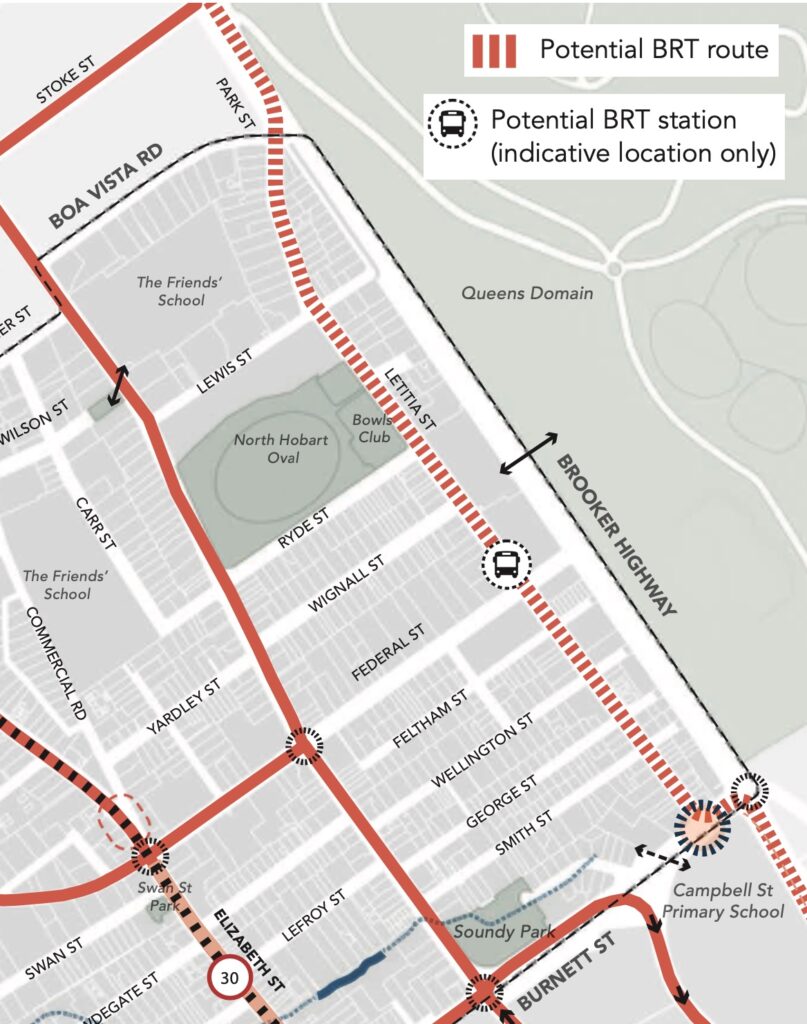

At New Town the northern corridor turns to follow the Brooker Highway before turning onto Letitia Street in North Hobart. It then continues down Campbell Street to reach the central interchange.

A potential site for a station is shown near Federal Street.

Southern corridor

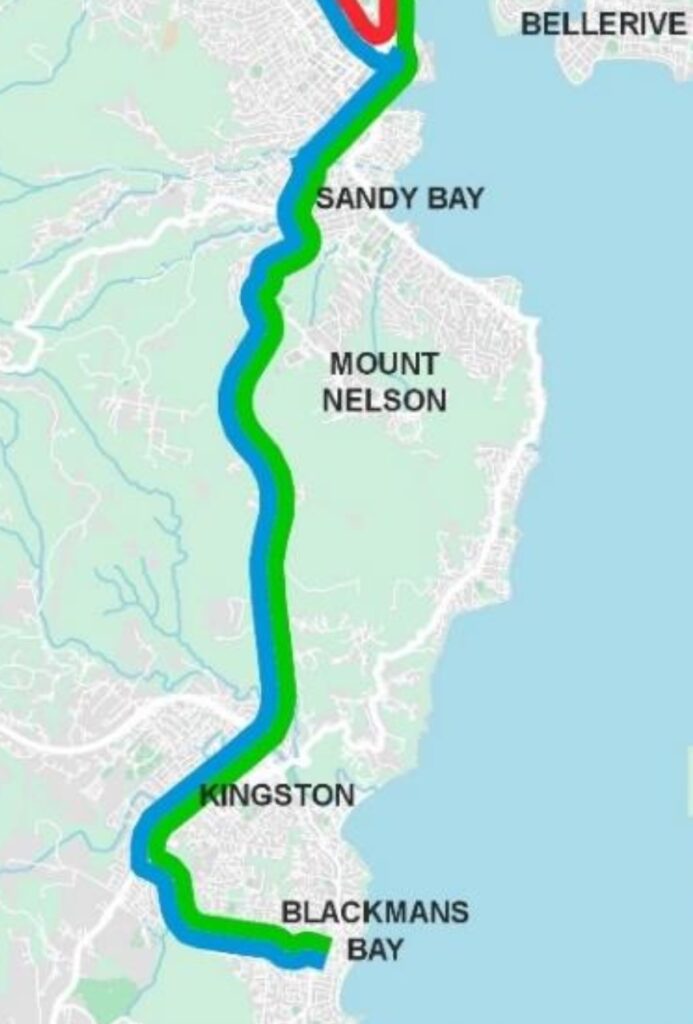

The southern corridor starts in Blackmans Bay and follows Algona Road to Kingston. From there it travels along the Southern Outlet, then Macquarie & Davey Streets through the city to the central interchange.

Already a number of projects are making changes that would facilitate the future addition of a dedicated bus lane on this southern corridor:

- The recent removal of parking and addition of a clearway on Macquarie Street.

- The transit lane connector currently being added between Macquarie & Davey Streets.

- The transit lane being added to the Southern Outlet with construction starting 2025.

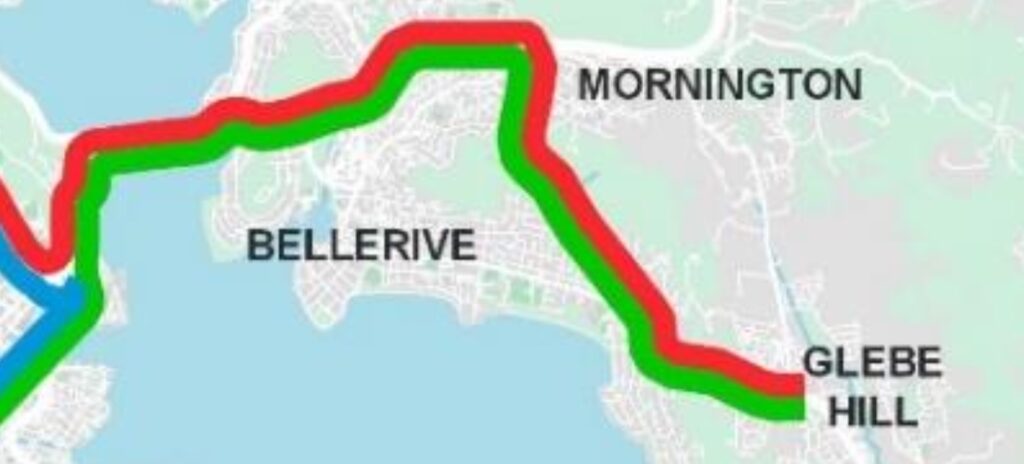

Eastern corridor

The eastern corridor goes from Glebe Hill along the South Arm Highway to Mornington. From there it takes the Tasman Highway past Warrane and over the Tasman Bridge to the central interchange.

Level of service

- Buses will go every seven and a half minutes during peak times.

- Outside of peak times, buses will go every fifteen minutes.

- Each bus will have a capacity for about 180 passengers.

Our thoughts

The good

- BRT could provide a high quality public transport network which is something that Hobart desperately needs. The current bus network is low quality — infrequent, slow & unreliable — and this is reflected in its low level of patronage. An expansion of the ferry network is coming but even with many more routes and the potential to extend the operating hours in future, ferries can only ever be an adjunct to a core public transport network. Getting more people to use public transport for more of their trips means less traffic congestion. It also means a transport system that is less prone to the massive disruption triggered by a minor crash or breakdown that is all too common now.

- The proposed routes would service a large proportion of Hobart’s population. Feeder buses and quality active transport connections would increase the catchment further. There’s also a lot of scope for extensions in future, for example to suburbs like Austins Ferry, Bridgewater, Rokeby, Lauderdale and Sorell. While some significant inner suburbs miss out — for example Lindisfarne, Bellerive, Sandy Bay, Taroona — many of these areas will be serviced by ferries.

- The network extends beyond the existing northern rail corridor. Through North Hobart instead of along the unpopulated area between the Domain and the river. To the south up the steep gradient of the Southern Outlet. Over the Tasman Bridge. It’s not clear how easily light rail could achieve this same network.

- BRT is relatively easy and cheap to implement compared to light rail. It’s tempting to think the existing rail line in the northern corridor would reduce the cost of light rail. However this condition report suggests all existing infrastructure including the rails and bridges will need to be replaced.

- It seems like underlying infrastructure is already being built. The third lane on the Southern Outlet and associated changes to Macquarie Street only really make sense if they will enable the future creation of a dedicated transit route.

The less good

- The government hasn’t yet made clear commitments to the project.

- Light rail would offer a higher quality service and evidence suggests would provoke more city shaping. Unlike Brisbane, Hobart has no existing bus lanes or busways so both BRT and light rail start on equal footing.

- When implemented well, BRT does approach light rail in terms of level of service. However BRT is much more susceptible to compromise resulting in a lower quality service. In particular, there’s a substantial risk that sections would not have dedicated busways or lanes due to concerns about impacts on general traffic. The Tasman Bridge is clearly vulnerable to this.

- The planning suggests the northern corridor would be one way with passing sections near stations. It’s difficult to see this resulting in an efficient system.

Where’s it at?

Bus rapid transit in Hobart is in an early planning phase.

The Macquarie Point stadium documents mention a WSP report titled Hobart Rapid Bus Service which was completed in 2023 but has not been made public. There is also mention of a business case in the process of being completed by DSG.

The Keeping Hobart Moving draft plan suggests planning during 2023-2026+ and delivery in 2023-2029+. The stadium documents talk about stage 1 of bus rapid transit services being in place in time for the opening of the stadium in 2029.

By way of an example, Brisbane’s bus rapid transit project went from concept design in 2018 to initial services starting in 2024 — about 6 years. Notably that project involved upgrading existing busways, not building routes from scratch.

More info

- Hobart City Deal — Activating the Northern Suburbs Transit Corridor — state government announcement

- Keeping Hobart Moving – Transport Solutions for Our Future — Draft

- Macquarie Point Stadium planning documents — Transport Study

- Hobart City Council — North Hobart Neighbourhood Plan

Very good report and explanation of BRT for Hobart. It certainly has a future for the Greater Hobart area such as a rapid connection to Kingston and Brighton for example. However a dedicated LRT corridor from (Elizabeth St Bus Mall) Hobart City to the Northern Suburbs would be far more city shaping and discourage developments in Green Fields areas. Greater Hobart is likely to reach at least 400,000 by 2050 – only 25 years away now. However errors for Hobarts population growth have been way off the mark until ABS released data in 2022 forecasting that Hobart would indeed reach 300,000 by 2032, instead of 2050! I’ve explored one option for a TBM LRT tunnel alignment of approx. 5 km / suit of 4 underground LRT stations – Hobart City, City Nth, Nth Hobart and New Town Plaza. Full grade separation to south of Berriedale Rd – via stations at Moonah, Derwent Pk, Showgrounds, Glenorchy, Montrose, Berriedale MONA, Connewarre Bay and a terminus at Claremont 12.75 km. When compared to the Riverline alignment this direct corridor to Hobart’s northern suburbs would be approx 1.5 km closer to the Hobart City node, beneath the Elizabeth Street Bus Mall and would operate at higher frequencies and be adaptable for full automation. The First Phase: Glenorchy to Macquarie Pt / Battery Pt (wire free network via Davey Street for example. I’m a Rail Futures Inc member in Victoria and former resident of Hobart. Working on a given Hobart LRT scenario which I will share later in 2025.

Do you think a BRT and LRT combination would complicate the network? Would mean interchanging between them in the city which could be avoided if it was BRT everywhere for example.

Look forward to hearing your further thoughts on LRT.

Combining LRT and BRT for the greater Hobart region would be a good solution for transformation of the Tasmanian capital into a more transit friendly city. However in the near future the Tasmanian Government with federal assistance will have to lay the ground works and planning for a city shaping LRT corridor directly from the city core to the Northern Suburbs to at least Glenorchy in Phase One. That’s where my scenario near completed for the so called Hobart Light Rail Metro should be implemented as the fundermental driver for transit orientation. I am happy to share some details of my scenario with you. Nonetheless the costly 5km tunnel and full grade separation via the existing Main Line rail corridor/ alignment will stimulate higher density housing perhaps modelled on the Nightingale housing developments. BRT will have an important role to reach those further suburbs utilising arterial roadways while LRT is required for urban renewal and city shaping Hobart.

Light rail for Hobart, great! What kind of trams would run on the light rail you propose, Sean? Like the trams in what city? Single and double articulated trams, like Melbourne has?

Thank you! This was very informative. This website is great and very useful resource 🙂

You’re very welcome!

The Tasmanian Government has outlined its proposed routes for BRT within saying much about what sort of busses would be traversing them. Such services are supposed to be a cut above ordinary bus services to encourage better uptake, these would be very expensive vehicles (relative to ordinary buses, though conventional buses aren’t that cheap either). Would it be entirely possible that the Tasmanian Government might try to do BRT on the cheap, by running conventional busses on the routes. Note no commitment to running these routes with electric vehicles either.

The Tasmanian government has an appallingly record when it comes to public transport and connectivity. Ironically the Cities of Hobart and Glenorchy for decades have shown great enthusiasm for better transport in the forn of LRT. The current state government and particularly its Transport Minister have no idea what go transport planning is all about. The state government lack the corporate memory for good public transport planning. That’s why they have thrown the vague BRT idea at the public. I fear they have no real plan and their idea may only eventuate into a few long distance articulated buses going out to outer suburban areas and encouraging developers to build on green fields as a short sighted solution to the shortage of affordable housing dilemma

I hope this becomes a reality. Down south we have a great Park and Ride at Huntingfield (and others) that could serve many on fast, reliable, comfortable services that aren’t hampered by regular traffic.

‘central interchange near the convergence of the Brooker Highway, the Tasman Highway’ – That’s not “central”. That’s on the periphery of the CBD.